Nairobi Planning Innovations has the pleasure of talking to Pedro B. Oritz, Senior Urban Planner at the World Bank. Pedro has been working for many years on the Nairobi Metropolitan Services Improvement Project (NaMSIP) which aims to strengthen urban services and infrastructure in the Nairobi metropolitan region. Pedro has a long and distinguished career in urban planning in Spain. He is the founder and Director of the Masters program of Town Planning of the University King Juan Carlos of Madrid, a former elected Mayor for Madrid’s Central District (1989-1991) and member of the Madrid’s City Council (1987-1995). Pedro also served as Director of the “Strategic Plan for Madrid” (1991-1994) and as Director General for Town and Regional Planning for the Government of Madrid Region. He is the author of the “Regional Development Plan of Madrid of 1996” and the “Land Planning Law of 1997” and recently wrote an important book on metropolitan planning The Art of Shaping the Metropolis. Today he talks to us about his work in Nairobi on commuter rail and metropolitan planning.

NPI: You have been working for NaMSIP for many years and have had a chance to explore how Nairobi and its surrounding counties and towns work. In the absence of metropolitan institutions, how do you see metropolitan planning working in practice in the Nairobi region?

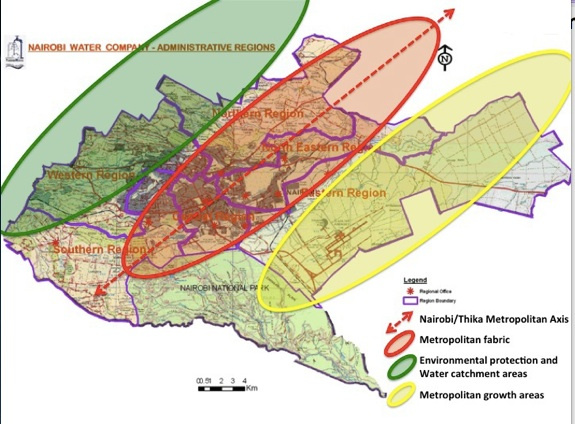

We started NaMSIP in March 2011. The idea was to produce a comprehensive cross-sectorial program that would integrate a metropolitan vision on public transport, land-use and water/environment, within a strategy of economic international positioning and response to local social needs.

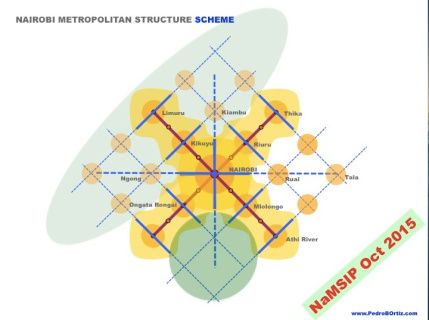

The basic metropolitan strategy was producing polycentrism to avoid the congestive dependency of the central CBD. This needs to be based in a renovated commuter rail system with urban centralities (TOD’s) along the three main existing lines and consistent strategic urban planning. Every town must have a different role to play complementing one each other. The periphery has to be reticulated, instead of orbital-designed, to provide homogeneous accessibility to maximize competitive potential.

I must say that Nairobi is the African leading metropolis in this metropolitan comprehensive approach. Many other African capitals will benefit from Nairobi’s leadership and experience. That will increase the leadership role of Nairobi as the capital of the African continent.

Nairobi is not circular. Ring roads and bypasses are not the solution. It has a very distinctive directionality, the borderline between Kiambu Hills and Athi River plain. The Metropolis has to be planned accordingly.

NPI: You have remarked that “Nairobi needs to play chess not darts” in order to relieve congestion. Can you explain what you mean?

Every town in a metropolis has to play it’s own role in a common strategy. That is the game of chess. Every piece has different movement tactics and that defines its role. Rooks are Thika, Athi River and Limuru. Knights: Tala, Kiambu and Ngong. Bishops: Riuru, Githurai, Imara Daima and Kikuyu. The Queen is obviously the international airport and the King the actual CBD. There will be in 30 years time another Queen. She will be the New south-central-station CBD, and this Queen will move progressively towards Makadara OuterRing road junction. Tala will become a Rook and Mlolongo and Ruai Bishops. Sorry if this sounds complex now, but metropolises are complex mechanisms. What must be clear is that Nairobi should not play the game of Darts anymore where everyone wants to reach the center and you get 3-hour jams. If Nairobi wants to be a world-class city, it has to play chess and not darts, which, by the way, is a much more intelligent game.

NPI: Under NaMSIP, there is a plan to upgrade commuter rail. Can you tell us what Nairobians can expect and what kinds of impacts this upgrade and expansion of commuter rail will have on the city?

To have an efficient metropolitan system you must have an efficient commuter/metro system. Nairobi is a 5 million inhabitant metropolis and will become a 14 million one. Those figures cannot just be served by BRT. BRT in Bogota (9 million) takes 2.5 hours to reach Chia from Soacha (25 km) and people riot. An efficient commuter service has trains every 10 to 15 minutes. Some are in the 3 minutes frequency. Now Nairobi has one train in the morning and another one in the evening. That is not a Commuter service. Figures have to move from ten thousand passengers a day to one million. Imagine taking a million future cars out of the streets of Nairobi. Now motorization is low: 1 car for every 10 people. But it is growing fast and will reach developed countries ratios of 7 cars for every 10 people. That means that Nairobi which now has 500,000 cars will have 10 million in the future. It is an impossible task to have an efficient metropolis if you don’t have an efficient public transport that will keep those cars out of the streets. All this requires an efficient commuter system, 60 trains per day in each line, a train every ten minutes. That requires a massive investment form KRC and the World Bank is helping on that. When will this happen? It depends on the management capacity of KRC and the political backing it has from Central Government. This is a national issue. Nairobi produces 50% of Kenyan GDP. If Nairobi works, Kenya works. National Government must be aware of that.

NPI: The majority of people use matatus today as their form of transport. What do you see as the future role of minibuses in the Nairobi region? How, if at all, will they link to the commuter rail project?

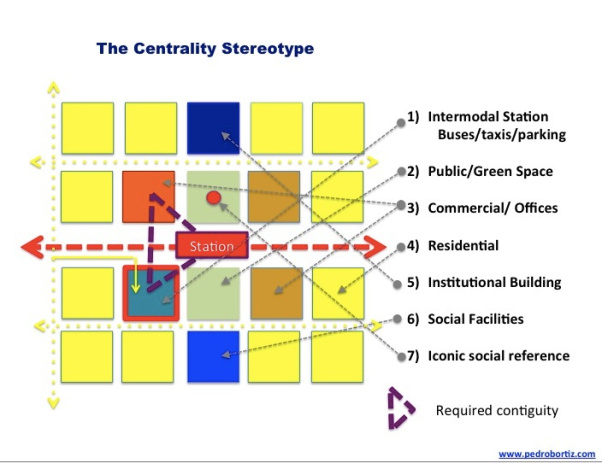

BRT’s, buses and minibuses are part of the comprehensive system of public transport. Each mode complements each other and plays a specific role. Minibuses are not made to run long distances. That is up to the train. The train has to feed matatus; matatus have to feed the train. Matatus must have efficient and comfortable intermodal stations at the train stations, and the trains will provide a million passengers to the matatus waiting there. The 100, 000 necessary matatus will take the passengers to their final destination a few kilometers away. Commuter rail and matatus do not compete. They complement each other in a win-win strategy. Columbia University is doing a wonderful job in this issue. We shall be working together for the years to come to make the whole system work.

NPI: There are a number of bus rapid transit (BRT) plans for Nairobi. In your view, what is the role of BRT in Nairobi and how would you like to see these projects link to the commuter rail and the matatu system?

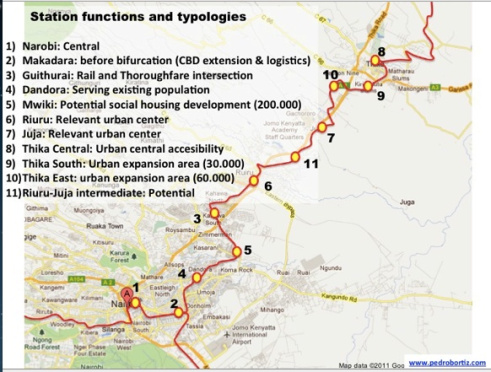

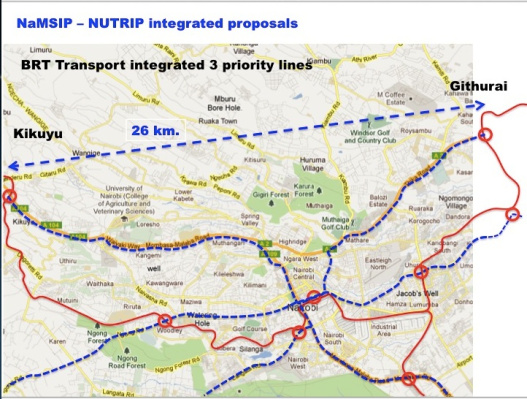

Again, BRT and trains must complement each other. For instance: I see BRT on Thika road with train intermodal connections in Githurai, Riuru, Juja and Thika. It is clear that BRT terminals have to coordinate with train stations: Imara Daima, Githurai, Kikuyu. Those are the actual priorities. The issue later will be if train and BRT can follow the same routes. A train stops every 2 km. BRT every 300 m. There could be a complementarity there, depending on the demand. If the demand is not high enough, then buses will be enough. You see: there is a lot of work to do to coordinate the whole public transport system of Nairobi. And future of the metropolis and the well being of the Nairobians is at stake.

NPI: You are working on transit-oriented development (“TOD”) around new commuter rail stations in Nairobi. Can you explain why TOD is important and the likely impacts of TOD for Nairobi?

A train station is not just a train station. It is an opportunity to serve the population that is using the train with complementary services. It is an excuse to fill the train with the population that is using/benefiting form those complementary uses. If 200,000 people are using a station, there are many possibilities to serve them right there or close by. Activities have to take place around the train stations: activities such as Social Facilities, Hospitals, Education, Administration, Commercial, Services, Offices, etc. On top of that you must provide a nice setting with public parks and public spaces for people to meet and enjoy themselves, plus the required intermodality to create easy access from other parts of the urban context. If all that has a high-density residential potential, then the whole thing will be a success as these people will have all those urban services at hand and those services will have the people they serve. This is what has been done in Europe since the implementation of the train in mid 19th C. London started that in 1850, Paris around the same time. The USA has branded the term TOD (Transit Oriented Development) from 1993 onwards. I guess we owe much to the ‘Millennials’ (young urban professionals that are changing the face of American cities by changing attitudes to car ownership). They get my gratitude from here. We are doing that in Nairobi. 32 centralities are being designed around 32 stations. The difficulty will be managing them. Land property is often not clear in Nairobi. Many times the private landowner does not see the benefits for him coming out of a public investment on transport and accessibility. He does not see his possibilities, or his duties. A lot of work has to be done in promoting that win-win dialogue and working together for the benefit of both the landowner and the public. Probably the legal system will have to be adapted and modernized. Professionals and stakeholders will need to be engaged. A huge task but essential if Nairobi wants to be an efficient, equitable and sustainable metropolis.

Parallel waterways flowing from Kiambu Hills to Athi River can support a sustainable green infrastructure network with parks, urban agriculture, storm water catchment reservoirs and environmental amenities.

NPI: Nairobi county has a Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) policy addressing walking, cycling and other forms of non-motorized transport. How important is NMT investment for Nairobi and its metro region?

The best way to access the commuter train is by walking or on bicycle. That means that this should be conveniently placed, close by and accessible. That is already a success. So to improve the accessibility via NMT to the station is a priority. As such we are working on this and improving access with quick-win investments on the NMT connection between the town centers and the train stations in 20 out of the 32 designed Centralities. Once this essential connection will be made. the NMT system can expand integrating the urban network and connecting further to the Green Infrastructure network based in the blue waterway assets of the Nairobi River effluents. This way transport, land use and environment will be integrated through the NMT network. It is the best way to make a sustainable focused integration.

The incrementalist approach to growing an NMT network across gray and green infrastructure networks will progressively integrate and serve the urban structure.

NPI: Where can citizens go to get more information on the NaMSIP plans?

NaMSIP has a coordination office on the 20th floor of Ambank Building. Excellent professionals are working there. They are there to serve Nairobi and the Nairobians. Don’t rush in numbers to ask them. They have to work. But you can reach out to them to ask for information. You also have the World Bank related webpages:

http://www.worldbank.org/projects/P107314/nairobi-metropolitan-services-improvement-project?lang=en

World Bank press release on NaMSIP

You can see as well some of the fertilizing ideas in this link: http://www.pedrobortiz.com/display-articles/listforcity/city/36 I hope you appreciate what you can see there, and I will be happy to discuss with anyone interested. My contact email is provided in the webpage. This interview has given me the idea that probably NaMSIP should produce a brochure, or a set of brochures, to inform easily to whoever wish to get more information. NaMSIP belongs to Nairobians and is working for their future. They should know. It’s their Right. Thank you very much for the opportunity to fulfill that Right.

An example of how Metropolises play Chess: The case of Madrid with towns characterized accordingly to their role on the overall metropolitan strategy. Sometimes the game will be won thanks to a pawn.

NPI: Thank you so much! I hope more planners will join the public conversation so that Nairobians can be informed and add their input into plans for their city.