By Lorraine Amollo Ambole

I have always wanted to grow my own food. But I live in the city of Nairobi, which is a concrete, dust, smog jungle. Would anything grow here? Well, apparently yes. According to the Mazingira Institute many people in Nairobi have been growing their own food in the city for decades. Not in the postmodern, allotment-garden, locavore kind of way. These urban farmers in Nairobi simply take advantage of any available space to grow food because it’s cheaper. It is the kind of urban farming that takes on from traditional subsistence farming, which is fairly common in rural areas of Kenya.

Nairobi’s many urban farmers use available space to grow food

Until the recent past, most Kenyans could lay claim to at least a small piece of ancestral land, which was then used to grow food. Following colonial rule by the British, some communities were removed from their ancestral land and thus denied their livelihoods as subsistence farmers. The country is now industrialising and many people pursue other livelihoods, although farming still remains a major occupation in rural and peri-urban areas.

As Nairobi expands, urban farming has become more and more difficult within the city. The urban population therefore largely depends on commercially produced food that is highly sensitive to international price shocks. Poor households are particularly vulnerable to maize price shocks as they spend about 20% of their food expenditure on maize. It is therefore not uncommon to find slum dwellers in Nairobi who can only afford one meal per day, if at all.

In answer to this glaring food insecurity problem, there are recent government supported initiatives in slums such as Kibera vertical farms. In such initiatives, slum dwellers learn how to grow vegetables in sacks, thus making use of the available spaces within the densely populated Kibera. In one area, a dumpsite has been converted into a thriving garden that provides cheaper vegetables for the locals and a decent income for the farmers. According to Real Impact, an NGO that offers training in urban farming, vertical bag gardening not only uses less space but also requires less water, less labour and is cheaper than conventional farming.

Women from Kibera sack farming

One major concern of having urban farms in poorly serviced slums like Kibera is the possibility of environmental contamination in the food. Studies already show that food grown in some of Nairobi’s slum areas are contaminated with heavy metals such as lead. Such revelations could scare off middle and high income earners who want to eat locally-produced organic food and to support urban farmers from slums.

In my case, this concern brings me back to the point that I should be growing my own food in my own sack that I can monitor closely. And there are already so many empty spaces around my neighbourhood, where I can place such sacks. I have even contemplated growing the food inside my own apartment though I don’t know how that would work. Everything I have tried to grow so far has died, including a cactus plant. I have a black thumb for sure. My poor horticultural skills aside, I think I’m onto something. I could perhaps start a social media campaign for people in my neighbourhood to become urban farmers.

Being the largest of its kind in Kenya, my neighbourhood: Nyayo Estate Embakasi, consists of over 2500 units that are currently occupied, and more than 2000 others that will be occupied in the near future. These units are mostly organised in blocks of 8 apartments that are clustered around shared spaces. Undoubtedly, there are excellent opportunities for community gardens within this vast estate. The residents in Nyayo Embakasi are more or less in the middle class, which means they can afford to buy their groceries, and might therefore worry little over food insecurity.

Nyayo Estate, Embakasi could be an excellent place for community gardens

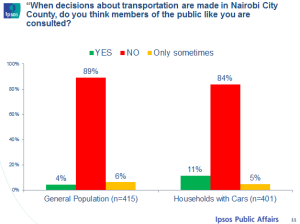

But like anyone else in Nairobi, they too would be interested in community engagement initiatives that promote sustainable lifestyles. Urban gardening in Nyayo would offer great opportunities for such engagement. The residents are already organised around issues of security and home ownership, and so it would not be a stretch for them to have community gardens. The estate guidelines however clearly stipulate that gardening is professionally managed by a designated firm, whose idea of gardening is flowers and grass that should not be stepped on. So my erecting sacks around the neighbourhood could be seen as a nuisance if not downright illegal.

It’s an idea worth considering though, and maybe other middle and high income areas would pick up on it, and green Nairobi and get their food while they are at it. As for the urban farming that’s ongoing in Nairobi slums, there is need to mitigate environmental contamination and ensure the produce is fit for consumption. The urban farmers in slums could also link up with organic food outlets outside of the slums so as to provide a steady market for their produce. Perhaps even the rooftops of commercial buildings in Nairobi can be used to grow food, if Nairobi County can pass a Paris-style legislation for greening rooftops in new commercial buildings. Nairobi, after all, has one of the highest growth rates per annum in Africa, and so sustainable food production should be at the top of our planning agenda.

Lorraine Amollo Ambole is a tutorial fellow at the School of the Arts and Design at University of Nairobi, Kenya. She is also a PhD candidate at the School of Public Leadership at University of Stellenbosch in South Africa. Her current research interests are: social design, community participation and transdisciplinarity. She also enjoys writing about Nairobi, her hometown. You can contact her about urban gardening in Nairobi at: [email protected] or [email protected].