Nairobi Planning Innovations is very pleased to interview Dr. David Nilsson, an urban environmentalist who has been working with long-term change and development issues in sub-Saharan Africa for the last 16 years. Now based in Sweden, he works as a consultant and as a researcher at KTH Royal Institute of Technology. David previously lived in Nairobi for many years and was involved in an important study by UN-Habitat and the Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA) on “Access to Water in Nairobi” . The project started in 2011 and generated important insights into equity issues as regards to water and sanitation access in the city. It will be the focus of our interview.

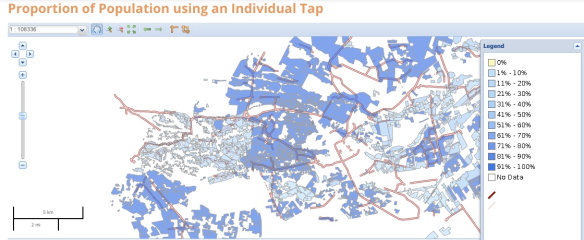

An estimated 64% of Nairobians have access to an individual or yard tap to access water

NPI: What was the motivation for doing the “Access to Water in Nairobi” project?

Just like so many other cities in developing economies, access to urban infrastructure services in Nairobi is extremely unequal. Reducing inequality is one of the most pressing challenges - perhaps the most pressing - if we are to live up to all nice words about human rights and sustainable development. The fact that huge inequalities persist in Kenya is an insult to the Bill of Rights. This project set out to develop an innovative method to analyse and visualise how large the service segregation is when it comes to water in Nairobi. But we also wanted to explain what is behind this inequality.

NPI: This research effort collected an impressive amount of data on water and household incomes. Can you briefly explain how you collected this data?

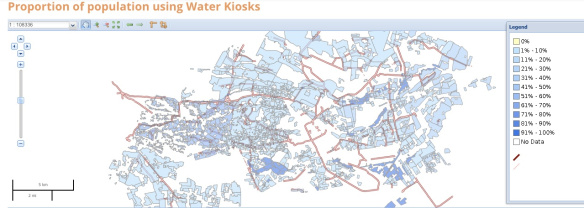

The project used a groundbreaking method, developed by IFRA, where open-source satellite images were spatially analysed and combined with a modest household survey sample of some 800 households. First of all, a set of characteristic indicators in the city landscape was identified, such as housing density, percentage of public space, tree cover, roofing material and so on. Using the satellite images, it was then possible to create a typology of different urban settings within the city based on these indicators. Once this ”map” of different urban types had been established, it was used to target the socio-economic survey. Being the first time we did this, a lot of work went into method development. But the method has a great potential for making the mapping of inequalities on the ground so much easier.

Nairobians in poor neighborhoods rely heavily on water kiosks (82%) or communal taps (24%). This means they often pay more for water than people in wealthier neighborhoods.

NPI: What were the most startling findings from this work?

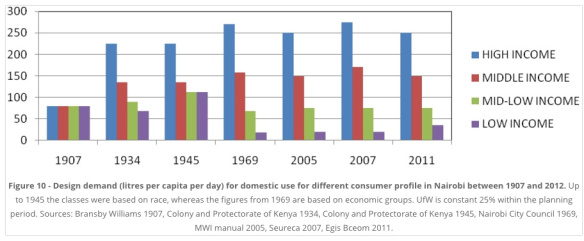

I think that what surprised me most was not the fact that the poorest people in Nairobi pay so much for the little water they consume – this is well known - but that the rich people consume so much and pay so little. In large parts of the city – typically in the upmarket areas to the West and Northwest – consumers use well above 160 litres per capita per day. This is in line with average consumption in well-watered regions of the world, like my home country Sweden. But Kenya is a water scarce country. And now we have the richest 10% of Nairobi’s population using 45% of all the water available for consumption. This made me reinterpret my understanding of Nairobi’s water challenge from one of scarcity and poverty, to a problem of unsustainable consumption by a rich minority.

NPI: What impact do you think your work has had on Nairobi? Do you think the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company will take into account the concerns raised about equity and wastage? Does it have incentives to do so?

The prime concern of the company is to improve economic performance and day-to-day operations, so it makes perfect sense for them to reduce wastage and illegal water use. But they have too few incentives to really focus on equity. It is the County, Athi Water Board, and the national regulator who need to create such incentives for the operator. Today the regulator, the Water Services Regulator Board (WASREB), ranks water operators almost exclusively on their economic performance. If the national regulator doesn’t take service equality seriously, why should the water company care? But I know that Nairobi Water and Sewerage Co is struggling to provide better service also to poor people. In the end, Nairobi’s one million unconnected offers a potential market, although the rich and already connected users of course is a much more lucrative market segment.

NPI: Based on your expertise and experience in Nairobi, including this project work, what are the most pressing interventions that need to happen if the city is “to achieve by 2030, universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all as well as access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all” (SDG 6)?

Several things need to happen as there is no universal cure. First of all, accountability in the sector has to be severely strengthened to root out corruption and to ensure that ordinary people’s voices are heard. Civil society will hence be crucial as watchdogs, but politicians and technocrats also need to show some leadership. Secondly, donor agencies need to put their money where their mouth is and stop funding large-scale supply-oriented solutions while there is still rampant inefficiency, wastage and inequality on the distribution side. Yes, Nairobi has recurrent water shortages. But large-scale bulkwater transfer solutions now advocated by the World Bank and others will first and foremost benefit rich Nairobians and foreign technology suppliers. Thirdly, we need locally engaged and genuinely committed research and development activity on the ground. Innovation actors in Nairobi can - and must - develop solutions that work here. Unfortunately there’s no off-the-shelf solution that can be imported to fix things up quickly.

NPI: What kinds of policies around Water and Sanitation should Nairobians advocate for in your view to achieve SDG6?

None. There is too much emphasis on policy development. I have studied the water policy landscape in Kenya since before the Water Bill of 1929. Nowadays, governments and donors seem to believe that to achieve a societal goal, it always starts with a policy or the passing of a law. At the same time we all know that enforcement and policy effectiveness is a totally different story. I think to achieve SDG 6, Kenyans should not spend another ten years refining policies and legislation, but instead nurture a vivid debate in society about equality, and if the city should be for everyone. A culture of accountability, of hard work and of “harambee”, is much more crucial than any policy in the world.

NPI: Thank you so much! I hope this interview will contribute to the needed debate on water and inequality in Nairobi. NPI readers can learn more from the Access to Water project here including the recommendations that came out of this work.